MICROBIAL INFECTIONS OF HUMANS(HUMAN MICROBIOLOGY CONTD..)

VIRUS AS PARASITES:

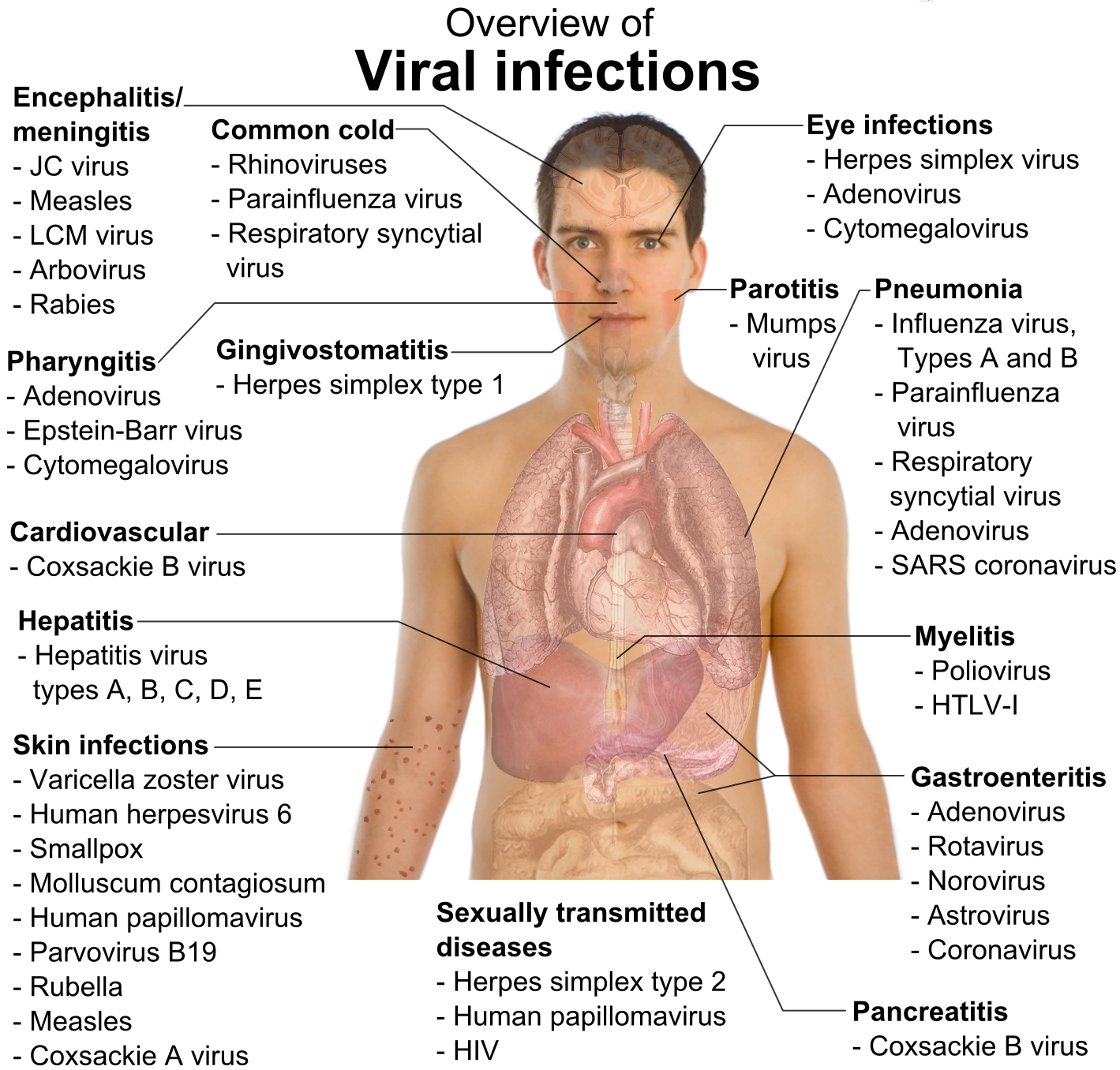

At a conservative estimate, there are at least thirty different viruses from fifteen taxonomic families that

are common causes of human illness. This number does not take into consideration the serological types

that exist in many of these viruses. So the common cold we are taking as one virus, whereas there are

over eighty serological types of rhinovirus. As every human will be infected by viruses in their lifetime,

we must concede that viruses are efficient parasites of humans. I am trying to outline some of the features of viruses that contribute to their success as human pathogens.

TYPES OF CLINICAL INFECTIONS:

The four broad types of viral infections recognised in humans. Because it is only those people with symptoms who come to our attention, it is easy to overlook the fact that most viral infections are asymptomatic. For the people who demonstrate clinical illness, the severity will range between mild and severe. The proportion of susceptible people who develop illness from those who are infected is called the attack rate, although it is not a true ‘rate’ and gives no indication of the total number of people infected.

The route of transmission does not fully account for the variation in attack rate between viruses, although clearly direct inoculation by parenteral transmission is likely to be more efficient in establishing an infection than transmission via aerosols. Unlike bacterial infections, many viral infections have a more damaging effect in older people compared to children. The childhood viral infections such as chickenpox and mumps are famously unforgiving in adults, whereas in children they cause rashes but otherwise usually fail to bother the child unduly. Why this should be is largely unknown.

Duration Extent Examples

Acute Local Rhinovirus,

Systemic Measles

Persistent Chronic Hepatitis B

Epstein Barr Virus

Latent Herpes Simplex Virus, Varicella zoster

Slow Bovine spongiform

encephalopathy

STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESSFUL VIRAL INFECTIONS:

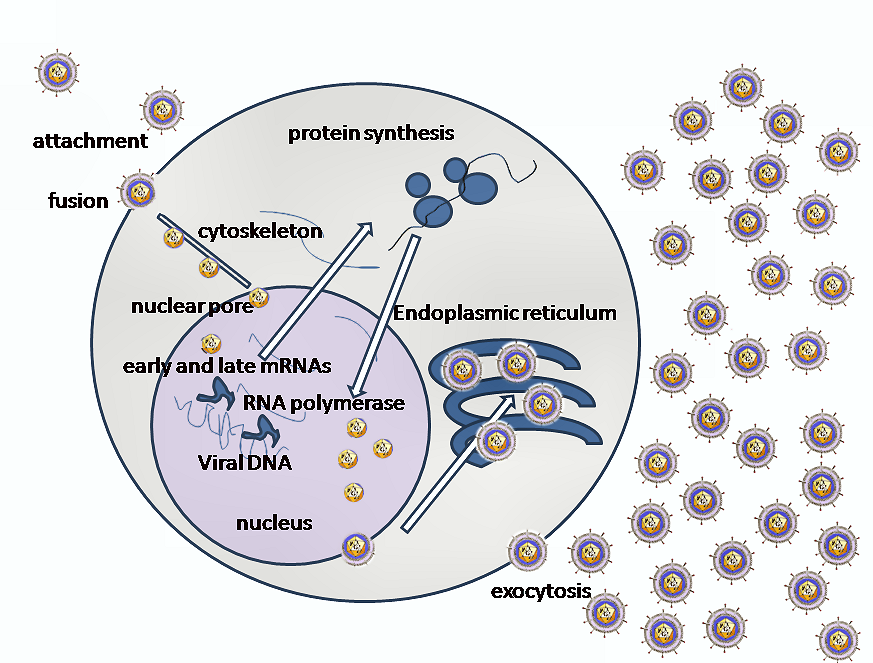

Successful? By this we mean reproductive success: able to replicate and persist within a population. As

obligate intracellular parasites, viruses have an absolute requirement for their host. If the virus causes

damage or even death of the host it must do so after it has had sufficient time to manufacture high

numbers of new viruses and release them into the environment. Note also that whilst many bacteria can

multiply in the environment without the requirement of animal tissue, viruses can only multiply in a

host. Periods spent in the environment are simply a holding event for viruses in which no multiplication

can occur. Viral replication can be seen from a perspective in which the availability of the host

determines the strategy adopted for infecting humans. In dense populations rapid and short periods of

replication serve to transmit the virus such that new (and readily available) hosts becoming infected. In

sparsely populated areas, the virus will need to produce virus over a longer period so that the few new

hosts that come into contact with the infected host can be infected. This distinction is reflected in two

broad groupings of viral infections of humans: acute and persistent.

The acute infections rely on rapid multiplication of virus in order to manufacture and shed (transmit)

new virus before the host has had time to mount a neutralising immunity. Examples will be measles and

influenza viruses, both RNA viruses and ones that require sufficient numbers of susceptible hosts in

order to maintain themselves in the community. With the measles virus, humans appear to be the only

host. With influenza virus, however, a wide range of animals can be infected and the virus is therefore a

zoonosis, periodically sweeping into town as an epidemic having transferred from an animal reservoir.

Persistent infections in the host (not the environment) are those in which the virus is not eliminated but,

having established itself, will persist for the lifetime of the host. The virus is either replicating at a very

low level continually, such as chronic hepatitis virus infections, or is latent for most of the time but

periodically undergoes a short burst of full replication in which infectious virus is manufactured and

released, e.g. Herpes simplex in cold sores. Many persistent virus infections are acquired as children with little or no pathology and then persist for life. This lifetime of infection will optimise the

chances of transmission, preferably to other children. Persistent infections, by definition, require that the

virus is maintained within the host cell and thus seeks to avoid killing the cell (is not cytolytic).

Integration of the viral nucleic acid into the host chromosome is an appropriate means to help promote

long-term survival in the host and avoid contact with the immune system which will also seek to destroy

the infected cells. Whilst persistent virus infections are mostly DNA viruses such as Herpes and

papillomaviruses, retroviruses will insert themselves as proviral DNA into the host genome following

reverse transcription from RNA and many retrovirus infections are persistent.

The differences in acute and persistent infections have consequences for antiviral treatments. Specific

antiviral chemotherapy will only have significant effects on persistent infections where there is

continued production of virus. In acute infections, the virus is produced in greatest numbers just prior to

the development of symptoms. By the time the patient has sought help, the virus is no longer in full

manufacture.

Other differences result from the properties of DNA and RNA viruses. RNA viruses have a reduced gene capacity compared with DNA viruses. DNA viruses often possess sufficient genetic space (several hundred

genes) such that roughly 50 per cent code for proteins that can interfere with the host immunity. RNA viruses do not have sufficient gene space and utilise genetic variation in order to generate new variants of virus.

STAGES IN HUMAN INFECTIONS

The key stages in the process of an infection are:

• entry into host,

• primary replication,

• spread within host,

• exit from host,

• evade host response.

ENTRY INTO HOST

The routes of transmission will depend on the site of the body that represent the exit site for the infectious virus. The exit of virus from the body can occur via several vehicles: urine, faeces, semen,

saliva, blood, milk, skin, squamous epithelia. Hepatitis B virus is released into the bloodstream from the liver and the transfer of infected blood is the major vehicle for transmission. Examples include the

sharing of needles amongst drug abusers and the accidental transmission following blood transfusion.

With hepatitis B the transmission is parenteral and therefore the virus cannot be transmitted by sneezing

or touching. Note how the site of multiplication (the liver) need not be the infectious site (blood).

Conversely, rhinoviruses, the aetiological agents of the common cold, multiply in the upper respiratory

tract epithelia and are transmitted via the secretions from the runny nose.

There are several ways of listing routes of transmission of infectious agents . The traditional list is as follows:

• aerosol,

• faeco-oral,

• parenteral (including vertical transmission),

• sexually,

• direct contact.

The routes of horizontal transmission can be related to the sites in the human body that represent the

major sites of entry:

• skin,

• gastrointestinal tract,

• respiratory tract,

• genito-urinary tract.

This list can be sensibly reduced by grouping the last three into one to yield three key routes of entry for

a virus into a new human host:

• Entry through mucous membranes: respiratory, genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts and the

conjunctiva.

• Entry through skin: insect bites (e.g. yellow fever virus); animal bites (e.g. rabies virus); skin to

skin (e.g. papillomavirus (warts, verrucas), Orf virus).

• Parenteral transmission: vertical transmission, direct inoculation into blood (needle, insect or

animal bite) or blood transfer through trauma (including sexual transmission).

Vertical transmission has clear advantages in that the foetus has the same blood supply as the mother

and has no defences against virus attack other than those present in the mother. One of the drawbacks of

vertical transmission is the risk of damaging the developing child in utero, i.e. foetal death and abortion.

A less extreme outcome is teratogenesis. Vertical transmission also includes transmission

via the germ line (i.e. through infected sperm or ovaries).

The properties of the virus will also influence those routes that are likely to be successful for the virus.

Viruses that cause gastroenteritis will need to resist exposure to gastric acid, bile acids and intestinal proteases if they are to reach the small intestine in any number and condition. As exemplified by rotaviruses, viruses causing gastroenteritis are not enveloped (which would be dissolved by bile acids) and tolerate acid pH and digestion by proteases. In fact, certain viruses are ‘activated’ by host proteases which act on surface proteins on the viral capsid. Numerous viruses that infect the respiratory tract are enveloped (notably influenza), reflecting the absence of lipid-dissolving secretions such as bile in the respiratory tract lining. For this reason the term ‘gastric flu’ is a misnomer. Influenza viruses cannot infect the stomach.

PRIMARY REPLICATION:

This depends on the site of entry: local infections will usually replicate at the site of entry. For example,

the rhinoviruses that cause the common cold will replicate in the epithelia in the nose and upper

respiratory tract. Local infections may invade the local lymph nodes but otherwise are restricted to the

site of entry. Systemic infections tend to have two-stage infection. The primary replication site serves as

an amplification of the virus from the small initial infectious dose and will be asymptomatic. Once the

virus has replicated at the local lymph node or epithelium, large numbers of virus are then released into

the bloodstream where they can attack the secondary tissues with corresponding tissue damage.

SPREAD WITHIN HOST:

The common cold will mostly restrict itself to the upper respiratory tract. Not all virus infections are

limited to localised infections but, instead, spread throughout the body (systemic infection) and have

secondary rounds of replication in other organs, yet not every cell in the body will succumb to viral

infection. The pathology and symptoms help distinguish different infections (e.g. rubella virus often

causes joint inflammation, whereas hepatitis viruses target the liver). The reason that viruses show such

tissue tropism(a restricted range of tissues that become infected) depends in part on the presence or

absence of appropriate receptor molecules on the host cell membranes and the relative permissiveness of

the cell type within that organ. This combination of factors means that the distribution of viral receptors

may be wider than any of the observed tissue tropism of the virus. Conversely, cell types other than

those in tissues displaying symptoms may be permissive for the virus but asymptomatic. Unless one

investigates all these other cells that may be infected, one can never be sure.

Many of the highly infectious virus infections of childhood (measles, chickenpox, rubella, mumps)

cause systemic infections reflecting rounds of viral replication in more than one organ of the body. The

virus enters at the appropriate site (skin, mucous membrane) and multiplies at the nearest available

tissue (e.g. epithelia). The virus spreads to the local lymph nodes from which it is released into the

bloodstream. This first viraemic phase carries the virus throughout the body and seeds the virus in

organs such as the liver, spleen and bone marrow. After a further round of multiplication, a second viraemic phase will deposit the virus in organs throughout the body. The second viraemia may be the

release of large numbers of virus into the bloodstream or the movement of virus within the cells of the

immune system (EBV, measles, HIV). The actual organ that is targeted from the secondary viraemia is

called the ‘target organ’ and will probably manifest itself in the symptoms. Only at this stage, however,

does overt disease become apparent with the patient showing signs and symptoms typical of the

infection in question. The childhood rashes seen with measles and chickenpox will appear following the

second viraemia. The exact cause of the viral rashes varies. Some rashes represent virus-infected cells being destroyed by the immune response, whereas others represent

blood vessel damage due to virus.

Having presented a generalised pattern of systemic viral infections, it is important to point out that

certain virus infections do not employ viraemic phases to spread through the body. Rabies virus moves

along the nerve fibres from the site of the bite towards the central nervous system. A significant

advantage of this pathway is the relative inaccessibility of the nervous system to immune surveillance

and the specific protection from the circulating antibodies, which cannot penetrate cells.

The different pathways taken by viruses in the course of an infection will often be reflected in the

incubation period. Local infections have shorter incubation periods (up to a week) whereas the systemic

infections incubate for 10 days or more. The important feature of this process is the long incubation

period during which the patient becomes infectious but shows no clinical disease. (The time from

between becoming infected and becoming infectious is called the ‘latent period’.) This is typical of

many viral infections, where the development of disease occurs after maximum numbers of virus are

being excreted. In this way transmission is favoured because the susceptible hosts are not running the

other way having seen the rash!

EXIT FROM HOST

What is the exit point from one host is likely to be the entry point for infection in the the next host. In

other words, the sites of viral replication will determine how and where the virus is transmitted to the

next host. Local infections will be shed from the local mucosa in secretions. The common cold is a

testament to the efficiency of the ‘secretions’. Blood-borne infections are that much more difficult to

transmit horizontally but nevertheless are able to escape through blood via insects, blood transfusion,

and trauma during sexual contact. A list of secretions that can contain viruses (saliva and nasal secretions, semen, milk, urine, vesicle fluids and faeces) does not take into account the duration of excretion of the virus, nor the numbers of virus, both of which can vary between virus depending on the strategy adopted. Is it better to shed large numbers of virus for a short while or smaller numbers over a longer period?

Cited By Kamal Singh Khadka

Msc Microbiology, TU.

Assistant Professor In Pokhara Bigyan Tatha Prabhidi Campus(PBPC), PU, PNC, LA, NA.

Pokhara, Nepal.

SOME SUGGESTED REFERENCES:

www.nativeremedies.com/ailment/types-of-viral-infections.html

www.merckmanuals.com/.../infections/viral_infections/overview_of_vira...

www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/Bhcv2/.../Infections_bacterial_and_viral?...

kidshealth.org/parent/infections/

www.meningitis.org/disease-info/types-causes/viral-meningitis

www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/viralinfections.html

www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/Bhcv2/.../Infections_bacterial_and_viral?...

cmr.asm.org/content/23/1/74.full

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12753686

www.patient.co.uk › Professional Reference

emedicine.medscape.com/article/211316-overview

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HIV/AIDS

cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/32/6/897.full?linkType=FULL...

At a conservative estimate, there are at least thirty different viruses from fifteen taxonomic families that

are common causes of human illness. This number does not take into consideration the serological types

that exist in many of these viruses. So the common cold we are taking as one virus, whereas there are

over eighty serological types of rhinovirus. As every human will be infected by viruses in their lifetime,

we must concede that viruses are efficient parasites of humans. I am trying to outline some of the features of viruses that contribute to their success as human pathogens.

TYPES OF CLINICAL INFECTIONS:

The four broad types of viral infections recognised in humans. Because it is only those people with symptoms who come to our attention, it is easy to overlook the fact that most viral infections are asymptomatic. For the people who demonstrate clinical illness, the severity will range between mild and severe. The proportion of susceptible people who develop illness from those who are infected is called the attack rate, although it is not a true ‘rate’ and gives no indication of the total number of people infected.

The route of transmission does not fully account for the variation in attack rate between viruses, although clearly direct inoculation by parenteral transmission is likely to be more efficient in establishing an infection than transmission via aerosols. Unlike bacterial infections, many viral infections have a more damaging effect in older people compared to children. The childhood viral infections such as chickenpox and mumps are famously unforgiving in adults, whereas in children they cause rashes but otherwise usually fail to bother the child unduly. Why this should be is largely unknown.

Duration Extent Examples

Acute Local Rhinovirus,

Systemic Measles

Persistent Chronic Hepatitis B

Epstein Barr Virus

Latent Herpes Simplex Virus, Varicella zoster

Slow Bovine spongiform

encephalopathy

STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESSFUL VIRAL INFECTIONS:

Successful? By this we mean reproductive success: able to replicate and persist within a population. As

obligate intracellular parasites, viruses have an absolute requirement for their host. If the virus causes

damage or even death of the host it must do so after it has had sufficient time to manufacture high

numbers of new viruses and release them into the environment. Note also that whilst many bacteria can

multiply in the environment without the requirement of animal tissue, viruses can only multiply in a

host. Periods spent in the environment are simply a holding event for viruses in which no multiplication

can occur. Viral replication can be seen from a perspective in which the availability of the host

determines the strategy adopted for infecting humans. In dense populations rapid and short periods of

replication serve to transmit the virus such that new (and readily available) hosts becoming infected. In

sparsely populated areas, the virus will need to produce virus over a longer period so that the few new

hosts that come into contact with the infected host can be infected. This distinction is reflected in two

broad groupings of viral infections of humans: acute and persistent.

The acute infections rely on rapid multiplication of virus in order to manufacture and shed (transmit)

new virus before the host has had time to mount a neutralising immunity. Examples will be measles and

influenza viruses, both RNA viruses and ones that require sufficient numbers of susceptible hosts in

order to maintain themselves in the community. With the measles virus, humans appear to be the only

host. With influenza virus, however, a wide range of animals can be infected and the virus is therefore a

zoonosis, periodically sweeping into town as an epidemic having transferred from an animal reservoir.

Persistent infections in the host (not the environment) are those in which the virus is not eliminated but,

having established itself, will persist for the lifetime of the host. The virus is either replicating at a very

low level continually, such as chronic hepatitis virus infections, or is latent for most of the time but

periodically undergoes a short burst of full replication in which infectious virus is manufactured and

released, e.g. Herpes simplex in cold sores. Many persistent virus infections are acquired as children with little or no pathology and then persist for life. This lifetime of infection will optimise the

chances of transmission, preferably to other children. Persistent infections, by definition, require that the

virus is maintained within the host cell and thus seeks to avoid killing the cell (is not cytolytic).

Integration of the viral nucleic acid into the host chromosome is an appropriate means to help promote

long-term survival in the host and avoid contact with the immune system which will also seek to destroy

the infected cells. Whilst persistent virus infections are mostly DNA viruses such as Herpes and

papillomaviruses, retroviruses will insert themselves as proviral DNA into the host genome following

reverse transcription from RNA and many retrovirus infections are persistent.

The differences in acute and persistent infections have consequences for antiviral treatments. Specific

antiviral chemotherapy will only have significant effects on persistent infections where there is

continued production of virus. In acute infections, the virus is produced in greatest numbers just prior to

the development of symptoms. By the time the patient has sought help, the virus is no longer in full

manufacture.

Other differences result from the properties of DNA and RNA viruses. RNA viruses have a reduced gene capacity compared with DNA viruses. DNA viruses often possess sufficient genetic space (several hundred

genes) such that roughly 50 per cent code for proteins that can interfere with the host immunity. RNA viruses do not have sufficient gene space and utilise genetic variation in order to generate new variants of virus.

STAGES IN HUMAN INFECTIONS

The key stages in the process of an infection are:

• entry into host,

• primary replication,

• spread within host,

• exit from host,

• evade host response.

ENTRY INTO HOST

The routes of transmission will depend on the site of the body that represent the exit site for the infectious virus. The exit of virus from the body can occur via several vehicles: urine, faeces, semen,

saliva, blood, milk, skin, squamous epithelia. Hepatitis B virus is released into the bloodstream from the liver and the transfer of infected blood is the major vehicle for transmission. Examples include the

sharing of needles amongst drug abusers and the accidental transmission following blood transfusion.

With hepatitis B the transmission is parenteral and therefore the virus cannot be transmitted by sneezing

or touching. Note how the site of multiplication (the liver) need not be the infectious site (blood).

Conversely, rhinoviruses, the aetiological agents of the common cold, multiply in the upper respiratory

tract epithelia and are transmitted via the secretions from the runny nose.

There are several ways of listing routes of transmission of infectious agents . The traditional list is as follows:

• aerosol,

• faeco-oral,

• parenteral (including vertical transmission),

• sexually,

• direct contact.

The routes of horizontal transmission can be related to the sites in the human body that represent the

major sites of entry:

• skin,

• gastrointestinal tract,

• respiratory tract,

• genito-urinary tract.

This list can be sensibly reduced by grouping the last three into one to yield three key routes of entry for

a virus into a new human host:

• Entry through mucous membranes: respiratory, genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts and the

conjunctiva.

• Entry through skin: insect bites (e.g. yellow fever virus); animal bites (e.g. rabies virus); skin to

skin (e.g. papillomavirus (warts, verrucas), Orf virus).

• Parenteral transmission: vertical transmission, direct inoculation into blood (needle, insect or

animal bite) or blood transfer through trauma (including sexual transmission).

Vertical transmission has clear advantages in that the foetus has the same blood supply as the mother

and has no defences against virus attack other than those present in the mother. One of the drawbacks of

vertical transmission is the risk of damaging the developing child in utero, i.e. foetal death and abortion.

A less extreme outcome is teratogenesis. Vertical transmission also includes transmission

via the germ line (i.e. through infected sperm or ovaries).

The properties of the virus will also influence those routes that are likely to be successful for the virus.

Viruses that cause gastroenteritis will need to resist exposure to gastric acid, bile acids and intestinal proteases if they are to reach the small intestine in any number and condition. As exemplified by rotaviruses, viruses causing gastroenteritis are not enveloped (which would be dissolved by bile acids) and tolerate acid pH and digestion by proteases. In fact, certain viruses are ‘activated’ by host proteases which act on surface proteins on the viral capsid. Numerous viruses that infect the respiratory tract are enveloped (notably influenza), reflecting the absence of lipid-dissolving secretions such as bile in the respiratory tract lining. For this reason the term ‘gastric flu’ is a misnomer. Influenza viruses cannot infect the stomach.

PRIMARY REPLICATION:

This depends on the site of entry: local infections will usually replicate at the site of entry. For example,

the rhinoviruses that cause the common cold will replicate in the epithelia in the nose and upper

respiratory tract. Local infections may invade the local lymph nodes but otherwise are restricted to the

site of entry. Systemic infections tend to have two-stage infection. The primary replication site serves as

an amplification of the virus from the small initial infectious dose and will be asymptomatic. Once the

virus has replicated at the local lymph node or epithelium, large numbers of virus are then released into

the bloodstream where they can attack the secondary tissues with corresponding tissue damage.

SPREAD WITHIN HOST:

The common cold will mostly restrict itself to the upper respiratory tract. Not all virus infections are

limited to localised infections but, instead, spread throughout the body (systemic infection) and have

secondary rounds of replication in other organs, yet not every cell in the body will succumb to viral

infection. The pathology and symptoms help distinguish different infections (e.g. rubella virus often

causes joint inflammation, whereas hepatitis viruses target the liver). The reason that viruses show such

tissue tropism(a restricted range of tissues that become infected) depends in part on the presence or

absence of appropriate receptor molecules on the host cell membranes and the relative permissiveness of

the cell type within that organ. This combination of factors means that the distribution of viral receptors

may be wider than any of the observed tissue tropism of the virus. Conversely, cell types other than

those in tissues displaying symptoms may be permissive for the virus but asymptomatic. Unless one

investigates all these other cells that may be infected, one can never be sure.

Many of the highly infectious virus infections of childhood (measles, chickenpox, rubella, mumps)

cause systemic infections reflecting rounds of viral replication in more than one organ of the body. The

virus enters at the appropriate site (skin, mucous membrane) and multiplies at the nearest available

tissue (e.g. epithelia). The virus spreads to the local lymph nodes from which it is released into the

bloodstream. This first viraemic phase carries the virus throughout the body and seeds the virus in

organs such as the liver, spleen and bone marrow. After a further round of multiplication, a second viraemic phase will deposit the virus in organs throughout the body. The second viraemia may be the

release of large numbers of virus into the bloodstream or the movement of virus within the cells of the

immune system (EBV, measles, HIV). The actual organ that is targeted from the secondary viraemia is

called the ‘target organ’ and will probably manifest itself in the symptoms. Only at this stage, however,

does overt disease become apparent with the patient showing signs and symptoms typical of the

infection in question. The childhood rashes seen with measles and chickenpox will appear following the

second viraemia. The exact cause of the viral rashes varies. Some rashes represent virus-infected cells being destroyed by the immune response, whereas others represent

blood vessel damage due to virus.

Having presented a generalised pattern of systemic viral infections, it is important to point out that

certain virus infections do not employ viraemic phases to spread through the body. Rabies virus moves

along the nerve fibres from the site of the bite towards the central nervous system. A significant

advantage of this pathway is the relative inaccessibility of the nervous system to immune surveillance

and the specific protection from the circulating antibodies, which cannot penetrate cells.

The different pathways taken by viruses in the course of an infection will often be reflected in the

incubation period. Local infections have shorter incubation periods (up to a week) whereas the systemic

infections incubate for 10 days or more. The important feature of this process is the long incubation

period during which the patient becomes infectious but shows no clinical disease. (The time from

between becoming infected and becoming infectious is called the ‘latent period’.) This is typical of

many viral infections, where the development of disease occurs after maximum numbers of virus are

being excreted. In this way transmission is favoured because the susceptible hosts are not running the

other way having seen the rash!

EXIT FROM HOST

What is the exit point from one host is likely to be the entry point for infection in the the next host. In

other words, the sites of viral replication will determine how and where the virus is transmitted to the

next host. Local infections will be shed from the local mucosa in secretions. The common cold is a

testament to the efficiency of the ‘secretions’. Blood-borne infections are that much more difficult to

transmit horizontally but nevertheless are able to escape through blood via insects, blood transfusion,

and trauma during sexual contact. A list of secretions that can contain viruses (saliva and nasal secretions, semen, milk, urine, vesicle fluids and faeces) does not take into account the duration of excretion of the virus, nor the numbers of virus, both of which can vary between virus depending on the strategy adopted. Is it better to shed large numbers of virus for a short while or smaller numbers over a longer period?

Cited By Kamal Singh Khadka

Msc Microbiology, TU.

Assistant Professor In Pokhara Bigyan Tatha Prabhidi Campus(PBPC), PU, PNC, LA, NA.

Pokhara, Nepal.

SOME SUGGESTED REFERENCES:

www.nativeremedies.com/ailment/types-of-viral-infections.html

www.merckmanuals.com/.../infections/viral_infections/overview_of_vira...

www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/Bhcv2/.../Infections_bacterial_and_viral?...

kidshealth.org/parent/infections/

www.meningitis.org/disease-info/types-causes/viral-meningitis

www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/viralinfections.html

www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/Bhcv2/.../Infections_bacterial_and_viral?...

cmr.asm.org/content/23/1/74.full

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12753686

www.patient.co.uk › Professional Reference

emedicine.medscape.com/article/211316-overview

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HIV/AIDS

cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/32/6/897.full?linkType=FULL...

Comments