HUMAN MICROBIOLOGY

FUNGAL PARASITES(CONTINUED)

A) CRYPTOCOCCUS NEOFORMANS:

Cryptococcus neoformans is a yeast that has become a frequent invader of patients with impaired cell mediated immunity, whereas clinical disease is rare in healthy people. In such patients the yeast often

invades the central nervous system and is particularly frequent in causing meningitis, although

pneumonia is not uncommon. The organism can be recovered from soil throughout the world, thus

differing from the primary pathogens described above which have a restricted geographical location.

Cryptococci will favour nitrogen-rich soil, typically achieved through bird droppings. There are approximately twenty species of cryptococci but only C. neoformans causes disease in humans.

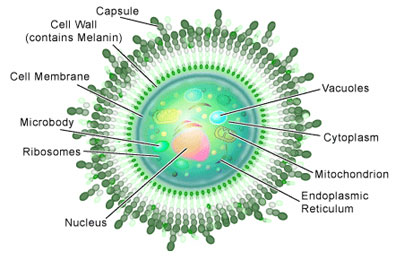

Unusual amongst fungal pathogens is the production of a polysaccharide capsule by C. neoformans. All

cryptococci can produce polysaccharide capsules but, when growing in soil, the capsule is usually not

evident. However, when nitrogen or moisture levels drop, capsule synthesis is stimulated. In this way the

capsule can provide a reservoir of water during an oncoming period of drought and protect the yeast from dehydration.

C. neoformans will grow at 37°C but most species of cryptococcus do not tolerate this

temperature, preferring ambient temperatures. Birds typically have body temperatures over 40°C and so,

whilst cryptococci might be carried in the avian gut, they do not cause illness in birds.

Humans are exposed to the organism via the respiratory tract. The dehydrated yeast cell will be of

sufficiently small diameter to act as an aerosol such that the yeasts may enter the respiratory tract,

whereas yeast cells with abundant capsule present will be too large to be effective aerosols. The increase

in carbon dioxide and fall in nitrogen concentrations that the yeast encounters once inhaled stimulate the synthesis of the capsule.

Cryptococcus neoformans will multiply within phagocytes, resistant to the antimicrobial

attack of the phagolysosome. As with bacterial capsules, the crytococcal capsule has a number of

functions: the polysaccharide capsule is a polymer of mannan, a typical component of fungal cell walls,

which is poorly immunogenic. The mannan appears to inhibit effective phagocytosis by the host

neutrophils unless specific antibodies are produced. The capsule is also a weak activator of the host

immune response if not intrinsically immunosuppressive. Shed capsular material will also act to bind

host antibody and complement components, thereby protecting the organisms itself.

Additional virulence factors have been suggested and the production of a phenoloxidase enzyme may

contribute to the neurotropism of the yeast. The phenoloxidase enzyme catalyses the conversion of

neurotransmitters such as dopamine, which are particularly abundant in brain tissue, into melanin.

Melanin acts as a scavenger for reactive oxygen species such as superoxide ion. This may protect the

yeast from such damage due to reactive oxygen species by leukocytes.

To keep perspective, it should be remembered that C. neoformans is rarely seen as a cause of disease in

healthy people despite the fact that many people are likely to encounter the organism. Only patients with

impaired or defective immune systems are likely to become ill with this organism. Interestingly, patients

with deficiencies in their cell-mediated immunity develop infections with this organism. These patients

are typically people with late stage AIDS and patients with immunosuppressive treatment for organ

transplant or autoimmune disease like Hodgkin’s disease. The role of the humoral arm of the immune

system is less clear. Significant antibody titres in serum do not appear to provide protection in these patients, which supports the critical role of the cell-mediated arm.

B) ASPERGILLUS INFECTIONS:

Aspergilli are moulds and, consistent with a free-living fungus, they are ubiquitous in the environment

where they can be cultured from soil, compost and grain. They are also easily cultured from foods and

plants in indoor environments. The abundance and small size of the spores produced (2–3 µm) means

that most people will encounter them as aerosols, able to penetrate the lower respiratory tract.

Fortunately, healthy people can deal with the spores, i.e. destroy or eliminate them, and hence do not

become ill, but the groups of patients who develop systemic illness with opportunistic fungi are

sufficiently immunocompromised that the spores are able to establish themselves within the host and

germinate into hyphae. Typically, Aspergillus infections occur in patients with prolonged and severe neutropenia (very low numbers of neutrophils in the blood) and often colonise pre-existing lesions such as old tubercular lesions or lung cancer sites. Of the numerous species within the genus, Aspergillus

fumigatus is the most frequent species isolated from patients with disease. Quite what distinguishes this

species from the rest, in terms of virulence capacity, is not known.

A. fumigatus grows across a broad temperature range (from 12–55°C), a feature which is an obvious

prerequisite for a free-living organism to multiply in the human host. The spores are thought to be more

resistant to the attack of neutrophils than the hyphae, and this might correspond with the need for severe

neutropenia in order for the organism to establish in the lungs. The spores are also adhesive to fibrin and

laminin components of lung tissues. Aspergilli, like all fungi, produce a number of proteolytic enzymes

such as proteases, phospholipases and elastases. As elastin is a major constituent of lung tissue, it is

suggested that such enzymes will facilitate penetration of lung tissue by the hyphae. The ease with

which Aspergilli can be cultured from the environment means that vulnerable patients in hospital wards

are continually exposed to Aspergillus spores, not least because building works are often ongoing in

hospital grounds. It has been recommended that special air filtration or positive pressure environments

are needed for bone marrow transplant patients but the expense is clearly substantial and the possible

protective benefits have not been shown.

RECOMMENDED READING

Cutler, J.E. (1991) Putative virulence factors of Candida albicans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol.45, 187–218.

Denning, D.W. (1991) Epidemiology and pathogenesis of systemic fungal infections in the

immunocompromised host. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.28, Suppl. B, 1–16.

Fridkin, S.K. and Jarvis, W.R. (1996) Epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections. Clin.

Microbiol. Rev.9, 499–511.

Hogan, L.H., Klein, B.S. and Levitz, S.M. (1996) Virulence factors of medically important fungi.

Clin. Microbiol. Rev.9, 469–88.

Kobayashi, G.S. and Medoff, G. (1998) Introduction to the fungi and mycoses, in Schaechter, M.,

Engelberg, N.C., Eisenstein, B.I. and Medoff, G. (eds) Mechanisms of Microbial Disease, 3rd

edition, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, USA.

Richardson, M.D. (1992) Fungal infections, in McGee, J.O.D., Isaacson, P.G. and Wright, N.A. (eds)

Oxford Textbook of Pathology, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Weitzman, I. and Summerbell, R.C. (1995) The dermatophytes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.8, 240–59.

Cited By Kamal Singh Khadka

Msc Microbiology, TU.

Assistant Professor In PU, PBPC,PNC, LA, NA.

Pokhara, Nepal.

A) CRYPTOCOCCUS NEOFORMANS:

Cryptococcus neoformans is a yeast that has become a frequent invader of patients with impaired cell mediated immunity, whereas clinical disease is rare in healthy people. In such patients the yeast often

invades the central nervous system and is particularly frequent in causing meningitis, although

pneumonia is not uncommon. The organism can be recovered from soil throughout the world, thus

differing from the primary pathogens described above which have a restricted geographical location.

Cryptococci will favour nitrogen-rich soil, typically achieved through bird droppings. There are approximately twenty species of cryptococci but only C. neoformans causes disease in humans.

Unusual amongst fungal pathogens is the production of a polysaccharide capsule by C. neoformans. All

cryptococci can produce polysaccharide capsules but, when growing in soil, the capsule is usually not

evident. However, when nitrogen or moisture levels drop, capsule synthesis is stimulated. In this way the

capsule can provide a reservoir of water during an oncoming period of drought and protect the yeast from dehydration.

C. neoformans will grow at 37°C but most species of cryptococcus do not tolerate this

temperature, preferring ambient temperatures. Birds typically have body temperatures over 40°C and so,

whilst cryptococci might be carried in the avian gut, they do not cause illness in birds.

Humans are exposed to the organism via the respiratory tract. The dehydrated yeast cell will be of

sufficiently small diameter to act as an aerosol such that the yeasts may enter the respiratory tract,

whereas yeast cells with abundant capsule present will be too large to be effective aerosols. The increase

in carbon dioxide and fall in nitrogen concentrations that the yeast encounters once inhaled stimulate the synthesis of the capsule.

Cryptococcus neoformans will multiply within phagocytes, resistant to the antimicrobial

attack of the phagolysosome. As with bacterial capsules, the crytococcal capsule has a number of

functions: the polysaccharide capsule is a polymer of mannan, a typical component of fungal cell walls,

which is poorly immunogenic. The mannan appears to inhibit effective phagocytosis by the host

neutrophils unless specific antibodies are produced. The capsule is also a weak activator of the host

immune response if not intrinsically immunosuppressive. Shed capsular material will also act to bind

host antibody and complement components, thereby protecting the organisms itself.

Additional virulence factors have been suggested and the production of a phenoloxidase enzyme may

contribute to the neurotropism of the yeast. The phenoloxidase enzyme catalyses the conversion of

neurotransmitters such as dopamine, which are particularly abundant in brain tissue, into melanin.

Melanin acts as a scavenger for reactive oxygen species such as superoxide ion. This may protect the

yeast from such damage due to reactive oxygen species by leukocytes.

To keep perspective, it should be remembered that C. neoformans is rarely seen as a cause of disease in

healthy people despite the fact that many people are likely to encounter the organism. Only patients with

impaired or defective immune systems are likely to become ill with this organism. Interestingly, patients

with deficiencies in their cell-mediated immunity develop infections with this organism. These patients

are typically people with late stage AIDS and patients with immunosuppressive treatment for organ

transplant or autoimmune disease like Hodgkin’s disease. The role of the humoral arm of the immune

system is less clear. Significant antibody titres in serum do not appear to provide protection in these patients, which supports the critical role of the cell-mediated arm.

B) ASPERGILLUS INFECTIONS:

Aspergilli are moulds and, consistent with a free-living fungus, they are ubiquitous in the environment

where they can be cultured from soil, compost and grain. They are also easily cultured from foods and

plants in indoor environments. The abundance and small size of the spores produced (2–3 µm) means

that most people will encounter them as aerosols, able to penetrate the lower respiratory tract.

Fortunately, healthy people can deal with the spores, i.e. destroy or eliminate them, and hence do not

become ill, but the groups of patients who develop systemic illness with opportunistic fungi are

sufficiently immunocompromised that the spores are able to establish themselves within the host and

germinate into hyphae. Typically, Aspergillus infections occur in patients with prolonged and severe neutropenia (very low numbers of neutrophils in the blood) and often colonise pre-existing lesions such as old tubercular lesions or lung cancer sites. Of the numerous species within the genus, Aspergillus

fumigatus is the most frequent species isolated from patients with disease. Quite what distinguishes this

species from the rest, in terms of virulence capacity, is not known.

A. fumigatus grows across a broad temperature range (from 12–55°C), a feature which is an obvious

prerequisite for a free-living organism to multiply in the human host. The spores are thought to be more

resistant to the attack of neutrophils than the hyphae, and this might correspond with the need for severe

neutropenia in order for the organism to establish in the lungs. The spores are also adhesive to fibrin and

laminin components of lung tissues. Aspergilli, like all fungi, produce a number of proteolytic enzymes

such as proteases, phospholipases and elastases. As elastin is a major constituent of lung tissue, it is

suggested that such enzymes will facilitate penetration of lung tissue by the hyphae. The ease with

which Aspergilli can be cultured from the environment means that vulnerable patients in hospital wards

are continually exposed to Aspergillus spores, not least because building works are often ongoing in

hospital grounds. It has been recommended that special air filtration or positive pressure environments

are needed for bone marrow transplant patients but the expense is clearly substantial and the possible

protective benefits have not been shown.

RECOMMENDED READING

Cutler, J.E. (1991) Putative virulence factors of Candida albicans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol.45, 187–218.

Denning, D.W. (1991) Epidemiology and pathogenesis of systemic fungal infections in the

immunocompromised host. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.28, Suppl. B, 1–16.

Fridkin, S.K. and Jarvis, W.R. (1996) Epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections. Clin.

Microbiol. Rev.9, 499–511.

Hogan, L.H., Klein, B.S. and Levitz, S.M. (1996) Virulence factors of medically important fungi.

Clin. Microbiol. Rev.9, 469–88.

Kobayashi, G.S. and Medoff, G. (1998) Introduction to the fungi and mycoses, in Schaechter, M.,

Engelberg, N.C., Eisenstein, B.I. and Medoff, G. (eds) Mechanisms of Microbial Disease, 3rd

edition, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, USA.

Richardson, M.D. (1992) Fungal infections, in McGee, J.O.D., Isaacson, P.G. and Wright, N.A. (eds)

Oxford Textbook of Pathology, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Weitzman, I. and Summerbell, R.C. (1995) The dermatophytes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.8, 240–59.

Cited By Kamal Singh Khadka

Msc Microbiology, TU.

Assistant Professor In PU, PBPC,PNC, LA, NA.

Pokhara, Nepal.

SOME SUGGESTED REFERENCES LINK:

Comments